Wednesday, June 29, 2011

The Ha of Ha

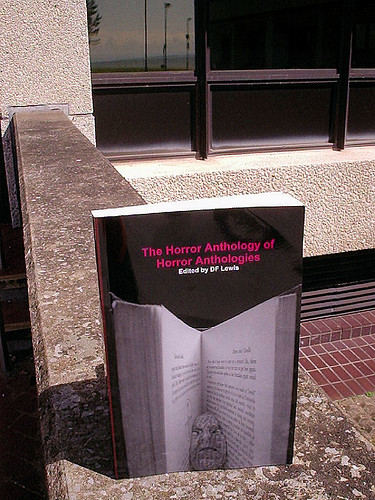

The legendary Des Lewis has put together another original anthology, this one boldly entitled The Horror Anthology of Horror Anthologies. The conceit behind the book is that all the stories are concerned with (fictional or real) horror anthologies. When the project was announced I didn't think I would have anything suitable for it, as I rarely write horror stories these days. But it occurred to me that I could rewrite one of my unpublished stories and turn it into something resembling a horror story. I did so and to my delight the story was accepted!

The legendary Des Lewis has put together another original anthology, this one boldly entitled The Horror Anthology of Horror Anthologies. The conceit behind the book is that all the stories are concerned with (fictional or real) horror anthologies. When the project was announced I didn't think I would have anything suitable for it, as I rarely write horror stories these days. But it occurred to me that I could rewrite one of my unpublished stories and turn it into something resembling a horror story. I did so and to my delight the story was accepted!'Tears of the Mutant Jesters' is about a horror anthology that suffers from appendicitis (an appendix is the vestigial organ found in some volumes that is a reminder of a time when books ate grass). This story is one of a growing number of adventures featuring a character named Thornton Excelsior that I have written in the past twelve months. I don't know from what psychological hinterland Mr Excelsior came from, but he seems to be muscling his way into all my weirdest tales. Maybe he's trying to take over the extreme surreal end of my oeuvre spectrum? Everyone needs to have at least one end of their oeuvre spectrum taken over from time to time...

My complimentary copy of The Horror Anthology of Horror Anthologies popped through my letterbox this very morning. It is available direct from the editor here and presumably will also be available on Amazon soon.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Weighing the Harpy

Originally I toyed with giving this blog post the title 'I'm Sorry I haven't a Clute' as a punning reference to the BBC Radio 4 comedy program, but it would be highly inaccurate, for the simple reason that I do have a Clute. The latest Clute in fact, Pardon This Intrusion, a collection of 47 essays, just published by Beccon Publications.

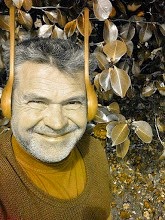

Originally I toyed with giving this blog post the title 'I'm Sorry I haven't a Clute' as a punning reference to the BBC Radio 4 comedy program, but it would be highly inaccurate, for the simple reason that I do have a Clute. The latest Clute in fact, Pardon This Intrusion, a collection of 47 essays, just published by Beccon Publications.John Clute (1940-2086?) is perhaps the most significant British critic of science fiction and fantasy. His reviews appeared in the legendary New Worlds magazine among many other places, and he is a multiple Hugo award winner for his outstanding encyclopedias, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. I think I might be included as an entry in the revised edition of the latter. If so, I'm chuffed, as I'm extremely fond of being an entry in encyclopedias!

Pardon This Intrusion features two essays Clute has written about my books. I'm delighted to report that he has given me permission to replicate one of these essays, which concentrates on my Worming the Harpy book. I am flattered and honoured to do so here. Ready?

*******************************************************

[John Clute's essay on Worming the Harpy]

Welcome to the first big room in the house of many mansions of Rhys Hughes, at last. It's about time. An earlier version of Worming the Harpy has of course already appeared – Tartarus Press's handsome but highly limited edition from 1995 – but for most of us that edition can have been little more than a rumour. A few copies were available on the net, it's true; but the cheapest of them – complete with torn dustwrapper — was listed at almost £170, or $300 plus. Undamaged copies were a lot more. Rhys Hughes may have benefited from the intense industriousness of presses like Tartarus, but their niche focus has clearly kept him from most of us.

Welcome to the first big room in the house of many mansions of Rhys Hughes, at last. It's about time. An earlier version of Worming the Harpy has of course already appeared – Tartarus Press's handsome but highly limited edition from 1995 – but for most of us that edition can have been little more than a rumour. A few copies were available on the net, it's true; but the cheapest of them – complete with torn dustwrapper — was listed at almost £170, or $300 plus. Undamaged copies were a lot more. Rhys Hughes may have benefited from the intense industriousness of presses like Tartarus, but their niche focus has clearly kept him from most of us.This cannot have entirely pleased Hughes; and for anyone interested in the literature of the fantastic at the cusp of century change, it has been extremely frustrating not to be able to start at the beginning of an enterprise – a career – so far iterated in what seem to be hundreds of stories, though it is hard to count. Partly this is a practical consequence of their fragmentary publication history over the fifteen or so years of Hughes's active career; more importantly, his avowed goal to write a thousand stories – each one of them somehow linked to all the others, a kind of rat-king whose roots adhere Eden to Jerusalem – turns out to be a good deal more than flamboyance. The echolalia one feels in the heart of a typical Hughes story is generated by at least two motors of referenciality. The first is the hyperlinking of story to story, so that each story reads, in part, like an eddy in the gnarly ocean of the whole.

But there is also the outside world. As with some other creators of works at home surfing the fractal chassis of the exceedingly strange era we are now passing into, Hughes seems to inhabit – to breathe the air of – almost any earlier writer one might think to recognize signalling up through the banyan of the thousand stories as they hit the open air out of their single root; in an introduction to his New Universal History of Infamy (2004), I mentioned echoes and transfigurations I thought I noticed from J B Morton to Italo Calvino, from Franz Kafka to John Sladek, from William Hope Hodgson to Michael Moorcock, from Franz Kafka to Ray Bradbury. I didn't mention E T A Hoffmann then, but would now – the title story, 'Worming the Harpy', plays his slow tunes hurdy-gurdy, hilariously – and I did mention Spike Milligan, and would again, because (I think) in these early stories Hughes exposes himself, rather more than in later work, to our recognition that his similarity to Milligan runs deeper than the occasional shared lurch of phrase, that he writes as though he'd been bloodied in the same wars Milligan fought for eight decades: the same up-yours melancholia about the malice of the absurd – about the absurdness of the world defined not only as an inherent lack of species-friendly grammar in the convulsion of the real, but also a sense that anyone who acts as though he believes what he is told by our Masters will almost necessarily inflict pain on others – that made Puckoon (1963) a very nearly great novel, and that made the five volume War Biography beginning with Adolf Hitler: my Part in his Downfall (1971) one of the funniest demolitions yet published of our cultural narratives. I'm sure I'm not the first one to think of Spike Milligan as a kind of gonzo Beckett; I would also suggest that Rhys Hughes also has what one might call a relationship of noise with Beckett: his response to the irrefutable Beckett mantra – I can't go on I must go on – being precisely that of going on. "You're going the wrong way" says Vladimir in Waiting for Godot (1952). "I need a running start" says Pozzo. "Stand back!"

Even at the beginning of his career, every story Hughes writes is cast into a cruel world; but, as with any writer one really cares about, each story is loved, and its betrayal into an awful world likely to destroy it is modestly similar to the Kabbalistic notion that, in order to get the stories of the universe going, God commits tsimtsum, a kind of harakiri withdrawal from the pleroma that gives the Real room enough to bang. God so loves the story of the world, in other words, that he tears himself into stories: which get devoured in Time. So it is with every writer worth reading, though some of them do continue to think the human world as having been told off from a divine principle. I think Rhys Hughes does not. I think every echo in every story that he tells is a kind of weapon thrown into the fray of a world that has come a long way from God's beginning Word: that Hughes's stories are about the noise of continuing to go on I can't go on I must go on, in a world that offers the pilgrim – the writer – the raw stinko stump of a protagonist whom we find again and again mouthing at us in one of the stories published here – nothing but broken grammars and apparatchik savageries.

This new edition of Worming the Harpy adds ‘The Forest Chapel Bell’, an excellent dies irae fantasy which fits better here. There are 17 tales altogether. Some of the shorter ones I find a bit garish and pun-driven: ‘The Man Who Mistook His Wife's Hat for the Mad Hatter's Wife’, a series of spoof turns on wordplays, derogates from Oliver Sacks's brilliant The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985), about an intensely moving case of visual agnosia, and from Michael Nyman's good opera of the same name. But the longer tales included here (I think Hughes's ideal length is the novella) are as good as some of his best later work: ‘A Carpet Seldom Found’ is an Answered Prayer story which cunningly and inexorably unpacks the fate it has in store for its greedy protagonist (Hughes's heroes are both oral and miserly: always male, usually solitary: collectors); and ‘The Good News Grimoire’ occupies pulp Europe with a jangly surety of touch, and it is also pretty funny. Hughes is in fact funny almost all the time, though it is sometimes easy to miss the sly joke in the rataplan. Here, from the hilarious exercise in taking things literally, ‘Cello I Love You’:

I have never been attractive to women, which is possibly why I mostly form relationships with inanimate objects. I have a single arm and a single leg and my stale green eyes are so close together that I am able to peep through a keyhole with both of them at once. Nor does my beauty lie beneath my skin; I have no skin.

So. Here is the first instalment, back with us at last and available, a first batch of tales tossed into the world machine. I have no idea if Rhys Hughes will ever finish telling his thousand, and to be honest I almost hope he stops counting. What I think I want is that the hurl of tales that begins here does not – short of that which stops us all – ever stop.

*******************************************************

Needless to say, I'm overjoyed with this interpretation. The comparison to Milligan is especially pleasing to me... The paperback reprint of Worming the Harpy is available directly from Tartarus Press or from Amazon and many other places... This very morning I decided to weigh the book as an experiment. Back in 1907 the maverick doctor Duncan MacDougall tried to weigh the human soul by placing the beds of dying patients on large weighing scales. He claimed a value of 21 grams for the human soul. Worming the Harpy weighs 360 grams, the equivalent of 17.14286 human souls; almost exactly the number of stories contained in the book! Coincidence? I think not! Bullcrap? Yes, probably.

Needless to say, I'm overjoyed with this interpretation. The comparison to Milligan is especially pleasing to me... The paperback reprint of Worming the Harpy is available directly from Tartarus Press or from Amazon and many other places... This very morning I decided to weigh the book as an experiment. Back in 1907 the maverick doctor Duncan MacDougall tried to weigh the human soul by placing the beds of dying patients on large weighing scales. He claimed a value of 21 grams for the human soul. Worming the Harpy weighs 360 grams, the equivalent of 17.14286 human souls; almost exactly the number of stories contained in the book! Coincidence? I think not! Bullcrap? Yes, probably.Anyway, John Clute is appearing tonight (June 21st) at the British Library, London, from 18:30 to 20:00, together with Michael Moorcock, Brian Aldiss and Norman Spinrad. Tickets for this event have probably sold out, but here's the relevant link anyway.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Shadow Play

I'm finally taking a break from writing fiction. I have been writing fiction non-stop since December 1991, so it's high time I had a rest. Indeed, I have been planning to have a rest for ages, but there always seemed to be one more project to complete. When you are me, there's always one more project to complete... Instead of concentrating on fiction, I'm going to do other things, such as messing about with music and getting much more fit. Last Saturday, Adele and I took part in our own customised pentathlon. We cycled, hiked, climbed, rock hopped (a noble sport from my youth) and enjoyed a dip in the sea. It was tough but invigorating exercise! After the pentathlon, we were shadows of our former selves. The proof of this can be found in these photos...

I'm finally taking a break from writing fiction. I have been writing fiction non-stop since December 1991, so it's high time I had a rest. Indeed, I have been planning to have a rest for ages, but there always seemed to be one more project to complete. When you are me, there's always one more project to complete... Instead of concentrating on fiction, I'm going to do other things, such as messing about with music and getting much more fit. Last Saturday, Adele and I took part in our own customised pentathlon. We cycled, hiked, climbed, rock hopped (a noble sport from my youth) and enjoyed a dip in the sea. It was tough but invigorating exercise! After the pentathlon, we were shadows of our former selves. The proof of this can be found in these photos... However, when I say I'm taking a 'break' from writing fiction, I don't mean a complete halt: it's more akin to an application of a 'brake' than a true 'break'; and like a bicycle moving at high speed, it'll take time for me to stop moving forward even when the wheels aren't spinning. So I'm still writing, but very slowly and without pressure: only when I feel like it (not every day). This means I will have more free time to sell my written but unpublished works (there are a lot of those) and also to promote more effectively those that have been published. For example: for anyone who speaks Italian, my latest ebook has now appeared in that language. Lo Sfarzoso Spettacolo Del Disordine is available from 40K . And I'll still be writing non-fiction, of course, as that's now my main source of income; and I need to save money to go travelling somewhere at the end of this year!

However, when I say I'm taking a 'break' from writing fiction, I don't mean a complete halt: it's more akin to an application of a 'brake' than a true 'break'; and like a bicycle moving at high speed, it'll take time for me to stop moving forward even when the wheels aren't spinning. So I'm still writing, but very slowly and without pressure: only when I feel like it (not every day). This means I will have more free time to sell my written but unpublished works (there are a lot of those) and also to promote more effectively those that have been published. For example: for anyone who speaks Italian, my latest ebook has now appeared in that language. Lo Sfarzoso Spettacolo Del Disordine is available from 40K . And I'll still be writing non-fiction, of course, as that's now my main source of income; and I need to save money to go travelling somewhere at the end of this year!Tuesday, June 07, 2011

The Enigma of Naipaul

That controversial Trinidadian, V.S. Naipaul, has been at it again, making comments that have aroused fury in certain corners of the writing world (does the writing world really have corners? I thought it was spherical). This time he has had the temerity to claim that no female writer is his equal... As might be expected, female writers have reacted angrily and sarcastically; and some male writers, keen to display their maturity (and eligibility?) in front of those female writers were even quicker off the mark, denouncing Mr Naipaul with all sort of curses and imprecations.

That controversial Trinidadian, V.S. Naipaul, has been at it again, making comments that have aroused fury in certain corners of the writing world (does the writing world really have corners? I thought it was spherical). This time he has had the temerity to claim that no female writer is his equal... As might be expected, female writers have reacted angrily and sarcastically; and some male writers, keen to display their maturity (and eligibility?) in front of those female writers were even quicker off the mark, denouncing Mr Naipaul with all sort of curses and imprecations.I find all this strange for one rather small but rigorously logical reason. Imagine that a hypothetical reader cites Naipaul as his favourite writer (I am sure there are real readers out there who regard Naipaul as their favourite writer). Hasn't that hypothetical reader made exactly the same claim on Naipaul's behalf that Naipaul himself made? When that reader says, "My favourite writer is V.S. Naipaul", he is simultaneously saying that no female writer can match him. Isn't that claim therefore inherently misogynistic?

And yet readers are happy to announce their favourite writers in public. Nobody expects any repercussions from doing so. My favourite writer is Italo Calvino. The moment I say that Calvino (a man) is my favourite writer I am automatically implying that no female writer is his match. Such exclusion is a logical consequence of having a favourite writer. It works the other way round. If (for example) Angela Carter was my favourite writer and I was prepared to say so aloud, I would be denigrating all male writers by making that claim.

Clearly absurdity lies this way. In Britain we still (just about) live in a society free enough to permit various forms of verbal and written dissent. We aren't forced to say 'socially acceptable' things all the time. It's not yet illegal to have forceful opinions. Naipaul's 'crime' (or 'sin') in this instance seems merely to be equivalent to listing himself as his own favourite writer. And yet, secretly, all writers regard themselves as their own favourite writer. How could they not? Does this mean that all male writers should be condemned for misogyny (and all female writers for misandry)?

I read a Naipaul novel many years ago, A House for Mr Biswas. It is vastly better than anything Jane Austen wrote. That's my opinion. If you don't like it, sue me in the Court of Fictional but Very Serious Crimes.

Wednesday, June 01, 2011

Don Cosquillas

The Pilgrim's Regress is finally finished! I started writing it in November 2007 when I was living in Spain; I completed the epilogue yesterday. At one point I thought this novel would never be done, but my fears on that score have proved groundless. Whether I can get it published is a different question entirely... What can I say about this particular novel? The twenty-four chapters follow the picaresque exploits of Arturo Risas, the self-styled Duque de Costillas y Cosquillas (better known simply as 'Don Cosquillas') and it's my most metafictional book so far; in fact it's not only a fiction about fiction but a metafiction about metafiction. Readers who don't like metafiction ought to stand clear!

The Pilgrim's Regress is finally finished! I started writing it in November 2007 when I was living in Spain; I completed the epilogue yesterday. At one point I thought this novel would never be done, but my fears on that score have proved groundless. Whether I can get it published is a different question entirely... What can I say about this particular novel? The twenty-four chapters follow the picaresque exploits of Arturo Risas, the self-styled Duque de Costillas y Cosquillas (better known simply as 'Don Cosquillas') and it's my most metafictional book so far; in fact it's not only a fiction about fiction but a metafiction about metafiction. Readers who don't like metafiction ought to stand clear!Don Cosquillas is a daft hero partly based on Don Quixote. The Don Quixote archetype is one of my favourites in literature. Together with the Odyssey archeytpe and the Robinson Crusoe archetype, it's the finest basic setup devised by any fictioneer. A great many of my stories utilise the Don Quixote archetype. I am therefore hugely indebted to Miguel de Cervantes! Another author I must credit for massive inspiration is James Branch Cabell, whom I discovered when I was a callow student a long time ago. I can't seem to escape Cabell; something to do with elective affinities perhaps? Other authors in a similar mode also hold a magnetic appeal for me: Ernest Bramah, Jack Vance, Manuel Mujica Láinez...

The Pilgrim's Regress is a standalone novel but it overlaps with some of my other story-cycles, especially my forthcoming Sangria in the Sangraal volume. In the epilogue the characters who have appeared in the novel put me on trial for the crime of using unnecessary wordplay in my prose and excessive contrivance in my plots. So I am forced to defend myself in the Court of Fictional but Very Serious Crimes! I don't have a photo of me standing in the dock. You'll have to make do with a photo of me standing in a fire instead... Don Cosquillas has to learn firewalking when he visits India, so maybe this picture illustrates that incident? I'll make a cardboard suit of armour soon and take some photos of me wearing that, for the sake of verisimilitude; but not this week!

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]