Friday, July 29, 2011

Old Tales From Spain: a real time review

The writer D.F. Lewis is not only the creator of outstandingly bizarre short stories and an influential editor of groundbreaking anthologies but also a tireless reviewer of fiction. One of his specialities is the so-called 'real time' review: criticism written on the hoof. In other words, he doesn't wait until he has finished a book before reviewing it. He reviews it as he goes along.

There are plenty of arguments against this custom. One might insist that it's impossible to have a proper perspective of a book that one is still in the process of reading. I don't care about that. I enjoy his 'real time' reviews and want to attempt one of my own. So that's what I plan to do... I have settled on a book: Felipe Alfau's Old Tales From Spain. I intend to start reading this work on Saturday (30th July) and I'll add relevant passages to this blog entry until a complete review is achieved.

I first discovered the writings of Felipe Alfau (1902-1999) exactly twenty years ago. I was in Cardiff library and took a chance on a paperback called Locos: a comedy of gestures. It turned out to be exactly the sort of fiction I like best. Although written in 1928 it wasn't published until 1936. It received rave reviews but quickly fell into neglect. Fifty years later, the editor Steven Moore of the wondrous Dalkey Archive Press discovered an old battered copy in a junkshop, read it, loved and decided to republish it. Given a second chance, Locos: a comedy of gestures proved to be a success. Alfau, who was living at the time in a New York rest home, was approached and asked whether he had any other manuscripts to offer. Yes, he had: the novel Chromos, which had been stashed in a cupboard since 1948.

I first discovered the writings of Felipe Alfau (1902-1999) exactly twenty years ago. I was in Cardiff library and took a chance on a paperback called Locos: a comedy of gestures. It turned out to be exactly the sort of fiction I like best. Although written in 1928 it wasn't published until 1936. It received rave reviews but quickly fell into neglect. Fifty years later, the editor Steven Moore of the wondrous Dalkey Archive Press discovered an old battered copy in a junkshop, read it, loved and decided to republish it. Given a second chance, Locos: a comedy of gestures proved to be a success. Alfau, who was living at the time in a New York rest home, was approached and asked whether he had any other manuscripts to offer. Yes, he had: the novel Chromos, which had been stashed in a cupboard since 1948.Since my first reading of Locos back in 1991 I have consistently placed Alfau among my top ten favourite writers. This might seem a little perverse, bearing in mind that he was one of the least prolific of authors. Indeed, he seemed to regard the act of writing fiction as something of minimal importance. His entire known output consists of two novels (Locos and Chromos), one collection of short stories (Old Tales From Spain) and a slim collection of poems Sentimental Songs... And yet there was something about Locos that filled me with enormous enthusiasm. Only a 'novel' in the loosest sense (the chapters are really more like linked short stories) it anticipates certain metafictional experiments by Calvino, Barth and Pavić. I think I read somewhere that Flann O'Brien was influenced by Alfau, though I'm not at all sure about this...

Although Spanish, Alfau wrote his three prose works in English and only recently have they been translated into Spanish. Locos remains his masterpiece: it is concise, luminous, funny, pure. In contrast, Chromos is a much more uneven book, sprawling and partly chaotic; and yet, for its wealth of invention and sheer originality, I am willing to state that it's my favourite Alfau book. Alfau himself, however, didn't much care for it. He wrote it secretly during work hours while he had a position in a bank. I'm not bothered about what an author thinks of their own work. I suspect that Chromos will be one of the small handful of books I will never give away.

Although Spanish, Alfau wrote his three prose works in English and only recently have they been translated into Spanish. Locos remains his masterpiece: it is concise, luminous, funny, pure. In contrast, Chromos is a much more uneven book, sprawling and partly chaotic; and yet, for its wealth of invention and sheer originality, I am willing to state that it's my favourite Alfau book. Alfau himself, however, didn't much care for it. He wrote it secretly during work hours while he had a position in a bank. I'm not bothered about what an author thinks of their own work. I suspect that Chromos will be one of the small handful of books I will never give away.The one Alfau book that has eluded me until now is his first, Old Tales From Spain, even though I once wrote a pastiche of the kind of story that might be found in that volume ('The Spanish Cyclops' in A New Universal History of Infamy). The truth is that I cheated: I wrote it 'blind', without really knowing what Old Tales From Spain was like; my story was influenced more by the style of Locos. I have always felt slightly uncomfortable about that trick. I rarely buy books these days (I want to unburden myself of possessions so I can go travelling again) but I decided it was finally time to make an exception for Old Tales From Spain. So I ordered it online from an American dealer called Basement Seller 101. Total cost of book and shipping? $24.47.

The book arrived within a week: much faster than I had anticipated. I tore open the packaging and was delighted to find a volume that radiated magic despite its battered and yellowing condition. The first thing I need to state is that it was published in 1929 by Doubleday as part of a series called 'Travel and Adventure for Young Folks'. Does this mean it's a book of children's stories? Yes, but after leafing through the volume it seems the tales are certainly sophisticated enough for adults too. The illustrations, of which there are many, are by Rhea Wells. I know nothing about this person; but whoever she was, she possessed superb drawing ability, not hugely dissimilar to that of the immortal Sidney Sime.

The book arrived within a week: much faster than I had anticipated. I tore open the packaging and was delighted to find a volume that radiated magic despite its battered and yellowing condition. The first thing I need to state is that it was published in 1929 by Doubleday as part of a series called 'Travel and Adventure for Young Folks'. Does this mean it's a book of children's stories? Yes, but after leafing through the volume it seems the tales are certainly sophisticated enough for adults too. The illustrations, of which there are many, are by Rhea Wells. I know nothing about this person; but whoever she was, she possessed superb drawing ability, not hugely dissimilar to that of the immortal Sidney Sime.(Sunday, 31st July)

Before dealing with the individual stories, I ought to stress that Old Tales From Spain is really quite an obscure book. I don't think the 1929 print run was large and it has never been reprinted; to the best of my knowledge it has never even been reviewed until now. I read the first story last night.

The Rainbow

The opening story features a nameless main character, a wanderer who arrives one day in a remote village. He asks for the cheapest room in a hosteria and is given a cramped space in the attic. It turns out that this penniless wanderer is a roving artist: he spends his days painting but never sells any of his work. Soon the innkeeper is demanding the money owed to him. Unable to pay, the artist offers to give the innkeeper's son free painting lessons. This arrangement works well for a time but eventually the inhabitants of the village tire of the artist and he decides to leave. He hurls his palette away but "to his great astonishment it described a semicircle in the sky, leaving a trail with all its colours in it standing brightly under the light of the setting sun." And so a solid rainbow is created, one that can accumulate dust and be washed clean again by the rain. Circumstances move rapidly after that: the artist is incarcerated for madness and dies in his cell; a wealthy art critic arrives and recognises the worth of his paintings. The story concludes with a metafictional twist as the resurrected artist begins to tell a story called 'The Rainbow'...

The opening story features a nameless main character, a wanderer who arrives one day in a remote village. He asks for the cheapest room in a hosteria and is given a cramped space in the attic. It turns out that this penniless wanderer is a roving artist: he spends his days painting but never sells any of his work. Soon the innkeeper is demanding the money owed to him. Unable to pay, the artist offers to give the innkeeper's son free painting lessons. This arrangement works well for a time but eventually the inhabitants of the village tire of the artist and he decides to leave. He hurls his palette away but "to his great astonishment it described a semicircle in the sky, leaving a trail with all its colours in it standing brightly under the light of the setting sun." And so a solid rainbow is created, one that can accumulate dust and be washed clean again by the rain. Circumstances move rapidly after that: the artist is incarcerated for madness and dies in his cell; a wealthy art critic arrives and recognises the worth of his paintings. The story concludes with a metafictional twist as the resurrected artist begins to tell a story called 'The Rainbow'...(Tuesday, 2nd August)

Having just read this online article about Alfau, courtesy of the Barcelona Review, I learned what I should have been able to work out for myself, namely that Old Tales From Spain was penned after Locos, not before. I had always assumed it was the other way around. Does this fact change my attitude to Old Tales? Yes, to a certain degree; we make allowances for our favourite writers and we are especially gentle when judging their earliest works. But Locos is a technically advanced text and Old Tales is therefore not the callow work of a beginner but the second effort of a talented professional (though Alfau didn't regard himself in that way at all).

Twilight

TwilightThe second story in the volume is far more fable-like in tone and subject than the first story. The Lady of Day and the Lord of Night are two spirits or demigods who control day and night, making sure that neither gets out of hand. They are fated to circle the Earth forever on opposite sides of the globe. But they fall in love with each other, leaving messages in the form of echoes in a particular garden. Finally, the Lord of Night decides to shrug off his destiny and stops in this garden, waiting for the sunrise. When it appears, the rays of the sun kill him, while the lingering shadows of his presence kill the Lady of Day. But their souls are joined together after death, which is the reason for the existence of 'twilight'. Rhea Wells' illustration of the Lord of Night has awakened an exceedingly dim memory in me. I'm sure I have seen this picture before, but I couldn't have: the book is far too obscure for that.

The Clover

This is quite an odd tale. It's absurd in every aspect and seems to mock itself. I have no idea if any of the pieces in Old Tales are genuine folk tales merely retold by Alfau or whether they are his originals. The reason for the fall of Granada, the last major Moorish stronghold in 15th Century Spain is explained as the culmination of a daring raid on the city by an inordinately lucky boy named Juanin and a talking goose called Juanon. A bag of four-leaf clover seeds helps this peculiar pair to outwit the mighty Musa-ben-Nessayr, who is presented not unsympathetically as a tyrant with a sentimental heart. Alfau deftly avoids a conventional fairytale ending by ensuring that Juanin refuses to marry the beautiful girl he has rescued. "...instead, he went back to his farm, taking all the clover with him, and they brought him so much good luck that he remained a bachelor and lived the happiest life to a very old age."

This is quite an odd tale. It's absurd in every aspect and seems to mock itself. I have no idea if any of the pieces in Old Tales are genuine folk tales merely retold by Alfau or whether they are his originals. The reason for the fall of Granada, the last major Moorish stronghold in 15th Century Spain is explained as the culmination of a daring raid on the city by an inordinately lucky boy named Juanin and a talking goose called Juanon. A bag of four-leaf clover seeds helps this peculiar pair to outwit the mighty Musa-ben-Nessayr, who is presented not unsympathetically as a tyrant with a sentimental heart. Alfau deftly avoids a conventional fairytale ending by ensuring that Juanin refuses to marry the beautiful girl he has rescued. "...instead, he went back to his farm, taking all the clover with him, and they brought him so much good luck that he remained a bachelor and lived the happiest life to a very old age."(Friday, 5th August)

I'm not an especially fast reader these days, or rather I tend to read more than one book at the same time (at the moment I'm reading no less than ten) and this means I usually proceed quite slowly through any particular volume. So after almost a week of reading Old Tales From Spain I am still only halfway through it. No matter: I am enjoying it and there's no rule that says a 'real time' review must be fast...

Sails

SailsA very 'pure' story that has the flavour of a Greek myth. It relates the adventures of a foundling who grows into manhood in a "primitive republic" that dominates the eastern coast of Spain "from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of the Lion". There is a strange timelessness about this piece because of the deliberate confusion of historical eras. The reader is simultaneously reminded of the Phoenicians and the Explorers of the time of Columbus, but in fact 'Sails' takes place in a forgotten age before the invention of sails, when all navigation was done "purely by the force of the arm." The foundling, Salvador, embarks on a mission to unite all the people who live on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea into a single nation; and he carries a special flag to symbolise his quest. This flag turns out to have a more practical function during a crisis...

The Feud

The most enjoyable story in the collection so far. Alfau lightens up considerably here and even allows himself some deft wordplay. "During the feudal days, the owners of those castles naturally had a feud..." The castles in question occupy two hills and belong to a pair of eccentric and reckless lords, Don Nuño and Don Pero. A feud has developed between them that will continue down through the generations until their descendants decide to enlist the aid of a sorceress in order to prevail. Don Nuño acquires the power to turn into a pigeon; Don Pero acquires the power to turn into a parrot. What follows is a delightful farce. This story contains the brilliant idea of crossbreeding carrier pigeons and parrots to obtain a new kind of bird that "instead of carrying the message, could speak it."

The most enjoyable story in the collection so far. Alfau lightens up considerably here and even allows himself some deft wordplay. "During the feudal days, the owners of those castles naturally had a feud..." The castles in question occupy two hills and belong to a pair of eccentric and reckless lords, Don Nuño and Don Pero. A feud has developed between them that will continue down through the generations until their descendants decide to enlist the aid of a sorceress in order to prevail. Don Nuño acquires the power to turn into a pigeon; Don Pero acquires the power to turn into a parrot. What follows is a delightful farce. This story contains the brilliant idea of crossbreeding carrier pigeons and parrots to obtain a new kind of bird that "instead of carrying the message, could speak it."(Sunday, 7th August)

I'm aware of how difficult it is to be a fan of Alfau; his entire output was tiny and he made no real effort to further himself in the world of literature. He just didn't seem to be particularly interested in fame. I set up a 'Fans of Felipe Alfau' group on Facebook a few years ago and it attracted 18 members. One of those members was Alfau's niece, which was a pleasant surprise.

The Legend of the Bees

The Legend of the BeesLike 'Sails' this has the flavour of Greek mythology. The outcome of this tale hinges on a fine example of imperfect symmetry (we must remember that Jorge Luis Borges claimed that imperfect symmetry is more pleasing to the human mind than perfect symmetry). Two races unknown to history invade Spain in the distant past. They have diametrically opposed cultures and neither is sustainable. Before disaster can destroy them, they learn from a foreign prophet how to merge their best qualities into a single organism that will endure. But not all the people choose this solution. Exactly half the members of each race decide to remain as they are: industrious and productive in the north, indolent and hedonistic in the south. Lazy generalisations are rarely welcome, but in this story they are an essential part of the dynamic.

The Witch of Amboto

This story is almost a conventional fairytale but Alfau has a twist up his sleeve. The action takes place near Guernica, where Alfau himself grew up, in the Basque lands: a beautiful and melancholy witch is in the habit of flying over cornfields and dropping her petticoats one by one onto the crops, which then wither and die, before flying home naked. The symbolism of this is intriguing! Urruchu is "the most stupid boy in town. He was proud of this title and had successfully defended it, testing his lack of wits against other boys from neighbouring villages in the last championship for all-round stupidity." This unlikely hero, who is refreshingly proud of his disability, manages to prevail over the witch after all the best archers in the Basque regions fail to bring her down. Like the villain in 'The Clover', the witch is depicted not unsympathetically, and this is refreshing.

This story is almost a conventional fairytale but Alfau has a twist up his sleeve. The action takes place near Guernica, where Alfau himself grew up, in the Basque lands: a beautiful and melancholy witch is in the habit of flying over cornfields and dropping her petticoats one by one onto the crops, which then wither and die, before flying home naked. The symbolism of this is intriguing! Urruchu is "the most stupid boy in town. He was proud of this title and had successfully defended it, testing his lack of wits against other boys from neighbouring villages in the last championship for all-round stupidity." This unlikely hero, who is refreshingly proud of his disability, manages to prevail over the witch after all the best archers in the Basque regions fail to bring her down. Like the villain in 'The Clover', the witch is depicted not unsympathetically, and this is refreshing.(Saturday, 13th August)

I have now been reading this book for two weeks. As an ordinary reviewer I really am rather slow; and as a 'real time' reviewer I must be rated as fairly hopeless. Yet I still regard this attempt as worthwhile... Having finally read two more stories in the collection, I am struck with how strongly Alfau is drawn to the theme of 'transformation'.

The Swan Song

The Swan SongA fairytale worthy of Hans Christian Andersen that relates how the Prince of Castile is too conceited and vain to find any woman beautiful or talented enough to be worthy of marrying him. From the four corners of the world come potential brides and he manages to insult them all, going so far as to tell the Princess of the South, who has arrived from a kingdom "just below the equator", that she is "ugly" (and unhappily we must speculate on who is responsible for this touch of racism: the fictional character or the xenophobic Alfau himself). In the end, after all the human princesses have been exhausted, a magical one turns up from an unknown fifth direction who is perfect in every way; but she rejects the prince's advances and punishes him. And yet, transformed into a swan, he is given one last chance to redeem himself...

The Weeping Willow and the Cypress Tree

I still don't know if the stories in Old Tales From Spain are retold folktales or Alfau's own inventions, but this one does feel genuinely ancient. It's one of the best pieces in the volume so far, partly for its symmetry and partly because its sentimental theme avoids becoming maudlin. Two trees in a garden have never noticed each other until they strike up a conversation one autumn day. The cypress tells the weeping willow that he was once a poor man who loved a rich girl; he went off to war to earn glory and they planned to marry when he returned. But the match was opposed by her father who used guile to trick her into marrying a wealthy lord instead. When the soldier returned and learned what had happened, he prayed in a sudden fit of misanthropy to be turned into a tree; and so he was. But the girl was so unhappy with her unwanted husband that she escaped and eventually ended up in the same garden, where she was also turned into a tree. And so finally they are reunited and the fact they are rooted in the ground proves to be no hindrance to a renewal of their relationship: "...and the wind blew his last leaves off and carried them to the shadowy waters, where the drooping branches held them in an embrace."

I still don't know if the stories in Old Tales From Spain are retold folktales or Alfau's own inventions, but this one does feel genuinely ancient. It's one of the best pieces in the volume so far, partly for its symmetry and partly because its sentimental theme avoids becoming maudlin. Two trees in a garden have never noticed each other until they strike up a conversation one autumn day. The cypress tells the weeping willow that he was once a poor man who loved a rich girl; he went off to war to earn glory and they planned to marry when he returned. But the match was opposed by her father who used guile to trick her into marrying a wealthy lord instead. When the soldier returned and learned what had happened, he prayed in a sudden fit of misanthropy to be turned into a tree; and so he was. But the girl was so unhappy with her unwanted husband that she escaped and eventually ended up in the same garden, where she was also turned into a tree. And so finally they are reunited and the fact they are rooted in the ground proves to be no hindrance to a renewal of their relationship: "...and the wind blew his last leaves off and carried them to the shadowy waters, where the drooping branches held them in an embrace."(Tuesday, 16th August)

I have finally finished the book. I am left feeling slightly melancholic as a result, partly because of the stories themselves, many of which had a nostalgic flavour, and partly because of the obscurity of the book itself. I'm fairly sure this is the only review Old Tales From Spain has ever had (if it isn't, I'd love to hear from someone who knows better.) I was left with a similar feeling after reading Lord Dunsany's Chronicles of Rodriguez, also set in 'old' Spain, but that's a much better known book, so maybe the comparison isn't so valid.

The Golden Worm

The Golden WormThe last story in Old Tales From Spain is one of the strongest in the volume. Six year old Lolita (and I always slightly wince when I hear that name) has never seen fireflies before. Her father tells her a story to account for their existence. In a variation of the famous Aesop story, it turns out that the insects who dwell in the grounds of a distant palace want a king of their own; they pray for one to appear and their wishes are granted. But in an Alfau story things are rarely straightforward. "Indeed, this was a real king. He did not move or speak or stir. He just lay there in his golden glory, oblivious of everything that was going on about him." There is a perfectly logical but unexpected reason for his extreme regal attitude. When he disappears one night, the insects search everywhere for him. In desperation, they even form "a special body of flies equipped with lights to search over the world at night. As a matter of fact they are still searching." And those are the fireflies. When Lolita asks, "Do you think, Father, they will ever find their golden king?" he answers in the negative. She asks why and he responds, "Because the story I have told you is not true."

A perfect ending to an enjoyable book.

But can I really recommend Old Tales From Spain to readers? Is it worth the effort of seeking out and reading? I'll just say that I'm an Alfau completist (not too difficult a task, as he only wrote four books) and I am delighted to have experienced his first published volume. But candidly I would say that the reader who is new to Alfau should obtain Locos: a comedy of gestures first. Indeed I regard that book as an essential for the shelves of all lovers of imaginative fiction. If the reader is impressed, then he or she should next seek out Chromos. That is probably sufficient.

As for the process of real time reviewing... I don't think I'm especially well suited to this style of reviewing. Speed is important in keeping the updates flowing and I'm too slow a reader. But I might give it another go some time in the future. Possible candidates for such reviews might be: The Novels of Friedrich Dürrenmatt, The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll and The Complete Firbank. But don't hold your breath...

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

That's Not My Name

I was amused recently to discover that my name had been spelled wrongly yet again in an anthology. The story 'All in a Flap' was apparently written by someone called Reece Hughes. When I read it, I was astonished to discover that it coincided word for word with one of my own stories!

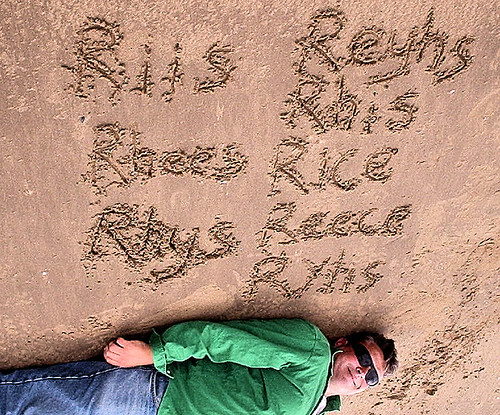

I was amused recently to discover that my name had been spelled wrongly yet again in an anthology. The story 'All in a Flap' was apparently written by someone called Reece Hughes. When I read it, I was astonished to discover that it coincided word for word with one of my own stories!Over the years my name has been spelled in a variety of ways. This photo demonstrates some of the variants that have appeared in print. Only one of them is correct. Can you guess which one?

Personally I don't regard my name as especially difficult to spell. After all, it's only four letters long. R-H-Y-S. It's a traditional Welsh name. I have been told that the lack of vowels might be confusing to anyone unfamiliar with the Welsh language but in fact the letter 'y' is a vowel in Welsh. As for pronunciation: my name rhymes with "fleece", but if you can roll the 'r' a little, that's even better.

The anthology in question is called Wacth -- sorry I mean Watch -- and it has been edited by Ian Faunkler -- sorry I mean Ian Faulkner -- and it's based on the theme of 'observation'. This photo shows it on the beach in front of Swansea Observatory, the most suitable location in the city I could find for the book... The daftest place in the world to site an astronomical telescope is Wales. Thanks to the perennial clouds, we have never seen the stars. We've only heard rumours. Points of light in the sky, apparently. I don't believe it.

The anthology in question is called Wacth -- sorry I mean Watch -- and it has been edited by Ian Faunkler -- sorry I mean Ian Faulkner -- and it's based on the theme of 'observation'. This photo shows it on the beach in front of Swansea Observatory, the most suitable location in the city I could find for the book... The daftest place in the world to site an astronomical telescope is Wales. Thanks to the perennial clouds, we have never seen the stars. We've only heard rumours. Points of light in the sky, apparently. I don't believe it.Thursday, July 21, 2011

A tribute to Михаи́л Булга́ков

Russia has produced more amazing writers than any other country in the world. Russia oozes talented authors in the same way that a man who is being chased by a bear oozes sweat and fear. It is unnecessary to mention the names of Tolstoy, Gogol, Pushkin, Lermontov, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov, Sologub, Akhmatova, etc. The Russian writer who has had the greatest personal impact on me is Vladimir Nabokov (to those who have only read Lolita I recommend some of his early works such as Glory and Despair). I am also a devotee of Yevgeny Zamyatin, Daniil Kharms and the Strugatsky Brothers. And even now I am discovering names of prodigous Russian talents previously unknown to me: Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky and Victor Pelevin, for example.

Russia has produced more amazing writers than any other country in the world. Russia oozes talented authors in the same way that a man who is being chased by a bear oozes sweat and fear. It is unnecessary to mention the names of Tolstoy, Gogol, Pushkin, Lermontov, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov, Sologub, Akhmatova, etc. The Russian writer who has had the greatest personal impact on me is Vladimir Nabokov (to those who have only read Lolita I recommend some of his early works such as Glory and Despair). I am also a devotee of Yevgeny Zamyatin, Daniil Kharms and the Strugatsky Brothers. And even now I am discovering names of prodigous Russian talents previously unknown to me: Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky and Victor Pelevin, for example.Why continue to drop names in this manner? The point is that one of the greatest of all Russian writers (perhaps the greatest of the 20th Century) was Mikhail Bulgakov; and Ex Occidente, the Romanian publishing house, has brought out a tribute anthology to that marvellous genius. I won't recommend specific works by Bulgakov here: they are all good. He was an expert at compressing a huge amount of action, thought and atmosphere into every page he wrote. One of his trademark techniques was to show scenes at slightly oblique angles, so that you don't quite "get" them immediately; there's always a delay before things click, but it's a very small delay, just like in real life. That's why he's ultimately a realist even though he writes (sometimes wild) satiric philosophical fantasy.

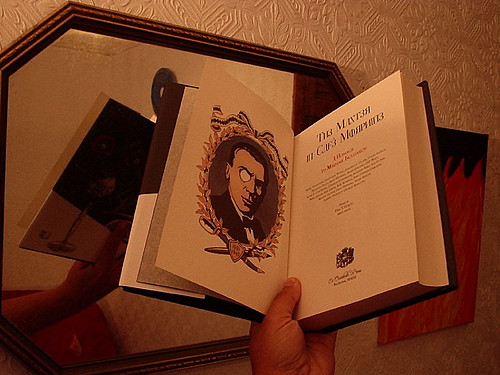

The Master in Café Morphine is a limited-edition deluxe volume featuring contributions from a score of writers. My own copy arrived yesterday and I haven't had a chance to read any of it yet apart from the Mark Valentine story (Valentine is always good). But I'm delighted to announce that this anthology contains one of my own stories, a 12,000 word novelette entitled 'The Darkest White' that seeks not only to engage with an imaginary Bulgakov but also with another writer from that era: the mysterious Lev Nussimbaum. It's an adventure story, both mystical and visceral, and is the most directly politcal tale I have ever attempted.

Saturday, July 16, 2011

Thirty Years Later

It occurred to me recently that I wrote my first proper short-story approximately 30 years ago. I can't remember the exact month, but I'm sure it was sometime in 1981. That story no longer exists but I do remember a few things about it. I recall, for example, that it was entitled 'The Journey of Mountain Hawk' and that it was based on a true historical incident: the ill-fated expedition of the conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in 1542. The main character of my story was based on 'The Turk', an Indian who offered to guide Coronado to the mythical city of Quivira where the people supposedly drank from golden cups hanging on the trees. Almost certainly 'The Turk' was attempting to trick Coronado and his men into the desert, in the hope they would get lost and die of thirst. Clearly he was willing to sacrifice himself in order to foil the plans of the invaders of his country and I was sufficiently impressed by the nobility and courage of this act to attempt my own fictional tribute... As can be seen above, Frederic Remington created a superb painting illustrating Coronado's expedition.

It occurred to me recently that I wrote my first proper short-story approximately 30 years ago. I can't remember the exact month, but I'm sure it was sometime in 1981. That story no longer exists but I do remember a few things about it. I recall, for example, that it was entitled 'The Journey of Mountain Hawk' and that it was based on a true historical incident: the ill-fated expedition of the conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in 1542. The main character of my story was based on 'The Turk', an Indian who offered to guide Coronado to the mythical city of Quivira where the people supposedly drank from golden cups hanging on the trees. Almost certainly 'The Turk' was attempting to trick Coronado and his men into the desert, in the hope they would get lost and die of thirst. Clearly he was willing to sacrifice himself in order to foil the plans of the invaders of his country and I was sufficiently impressed by the nobility and courage of this act to attempt my own fictional tribute... As can be seen above, Frederic Remington created a superb painting illustrating Coronado's expedition.I have absolutely no idea what my second short story was about, nor my third, fourth, fifth, sixth. Everything I wrote before 1989 has been lost. I do know, however, that the themes I chose were generally beyond my abilities. Having said that, I still occasionally milk those early ideas; and occasionally I rewrite (from memory) tales that I originally produced in my mid teens, the most recent example being 'The Gargantuan Legion', a sort of absurdist spaghetti western featuring living skeletons and a lasso made from a halo. Other stories in my offical canon that are rewrites of juvenile efforts include: 'Death of an English Teacher', 'The Forest Chapel Bell', 'The Falling Star', 'Zumbooruk', 'The Chimney', 'Learning to Fall', 'The Evil Side of Reginald Burke', 'The Desiccated Sage', 'Castle Cesare', 'Nightmare Alley', 'The Yeasty Rise and Half-Baked Fall of Lyndon Williams' and several others. The original versions were all written before the age of 16. I can only hope that the rewrites are superior, but who knows?

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Cabinet of Curiosities

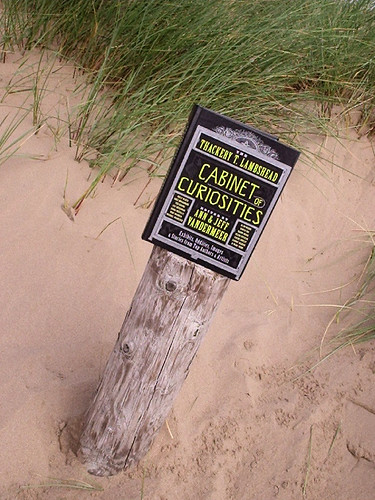

The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities is another of the VanderMeers' hare (and aardvark) brained projects... Thank the gods of whimsy that some editors with true proper imaginations still exist on the surface of the Earth... When Jeff and Ann are behind a project, you can almost guarantee that it's going to be interesting, unusual and broader in inventive scope than most other (conventional) fiction anthologies...

The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities is another of the VanderMeers' hare (and aardvark) brained projects... Thank the gods of whimsy that some editors with true proper imaginations still exist on the surface of the Earth... When Jeff and Ann are behind a project, you can almost guarantee that it's going to be interesting, unusual and broader in inventive scope than most other (conventional) fiction anthologies...This one is an independent follow-up to the cult classic The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, a Hugo Award and World Fantasy Award finalist… Notable contributors include Ted Chiang, John Coulthart, Rikki Ducornet, Amal El-Mohtar, Jeffrey Ford, Lev Grossman, N.K. Jemisin, Caitlin R. Kiernan, China Mieville, Mike Mignola, Michael Moorcock, Alan Moore, Garth Nix, Naomi Novik, James A. Owen, Helen Oyeyemi, J.K. Potter, Cherie Priest, Ekaterina Sedia, Jan Svankmajer, Rachel Swirsky, Carrie Vaughn, Jake von Slatt, Tad Williams, Charles Yu, and many more... Oh yes, and I've got a very short piece in there too. This book is available from Amazon and elsewhere.

Tuesday, July 05, 2011

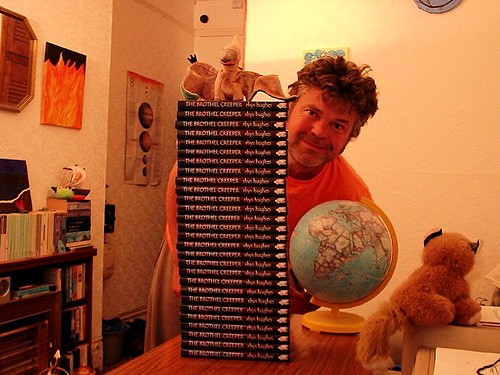

A Brothel Creeper Tower

There are exactly 28 copies remaining of the signed limited-edition hardback version of The Brothel Creeper. Here they are, arranged into a tower! It's not a very high tower, but as Primo Levi reminds us, "How much taller than a high tower is a very high tower?" Among these 28 is numero uno, number one! I was instructed by the publisher to keep it in reserve for a customer, but the customer has dawdled an awful long time about purchasing it, so I reckon it's up for grabs... 28 is an interesting number. In fact it's one of my lucky numbers, partly because it's a perfect number (a positive integer that is equal to the sum of its proper positive divisors) and partly because it's the atomic number of nickel, a cheeky little metal. Twenty-eight also has associations with the moon and ladies.

To purchase one of the books on this tower, please visit the relevant Gray Friar Press webpage here. If you want that number one, please specify that you do. If number one is at the bottom, the tower will fall down. Oops... What else? Oh yes, there's a chap called Steven Lockley. To increase traffic to his blog via the old economic principle of "trickle down" he is running guest blogs by various writers. Tim Lebbon has done one, so has Stephen Volk, Paul Finch, Gary McMahon, etc. My own guest blog has just appeared and it's about metafiction. Enjoy!

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]